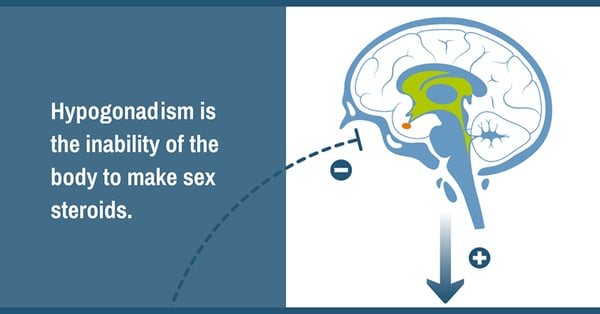

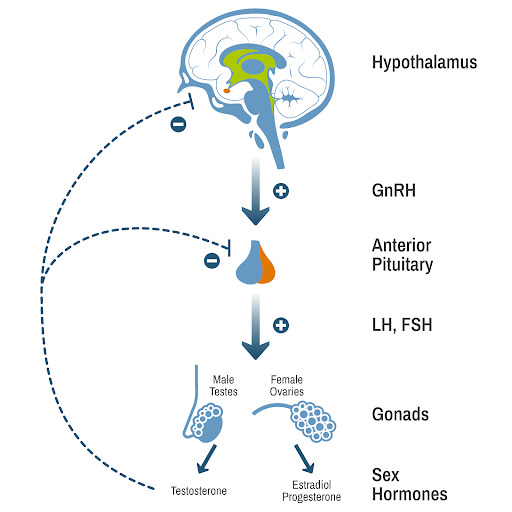

When someone has hypogonadism, the sex glands (gonads) do not adequately produce sex hormones. In males, that hormone is testosterone. In females, it’s estrogen and progesterone.

Hypogonadism is quite common among people with Prader-Willi syndrome, and if it goes untreated, it can cause lasting health problems.

That’s why it’s important to recognize the symptoms and understand the science behind the most common treatment for this condition.

When a typically developing body reaches puberty, the brain starts to send out signals to the ovaries or testes to make estrogen or testosterone. When someone has hypogonadism, the signals are not sent, or the ovaries or testes are not able to respond to them.

The result is that the body does not produce the hormones needed for typical development.

There are two types of hypogonadism:

Hypogonadism is common in Prader-Willi syndrome (PWS), affecting at least half the people who have been diagnosed with the genetic disorder, and may be a combination of primary and/or secondary hypogonadism.

Our go-to expert on hypogonadism is Dr. Diane Stafford, pediatric endocrinologist and member of the PWS Clinical Investigation Collaborative, a group of clinical researchers, health care providers, and patient advocates working to improve care for people with PWS.

In a two-part video series for FPWR, Dr. Stafford provides an overview of the condition, addressing some of the most common questions about hypogonadism and sex steroid therapy.

Part 1 focuses on hypogonadism and the effect it has on the body. The second video covers more details on hypogonadism in the PWS population and explores treatment options.

The following symptoms are associated with hypogonadism:

In PWS, hypogonadism can present in several ways.

Scientists believe that hypogonadism in PWS is a result of the same hypothalamic dysfunction that causes growth hormone deficiency, hyperphagia, and other issues common in PWS.

However, they also speculate that the condition might be more complicated, as they are seeing some evidence of dysfunction involving the ovaries or testes as well.

Hypogonadism is a common symptom of PWS and affects both boys and girls. It is estimated that hypogonadism occurs in about 50% of people with PWS, but data has been difficult to obtain, and the true incidence may be higher, according to a review published in 2021.

Just as male and female development diverge during puberty, hypogonadism has different effects on males and females with PWS. The symptoms do overlap, however.

A study that included a cohort of 57 Dutch men with PWS found that untreated male hypogonadism can make a number of health issues worse for people with PWS: muscle weakness, obesity, osteoporosis, and fatigue. An expert panel developed treatment recommendations for men with PWS.

A Dutch study of female adults with PWS found that hypogonadism was frequent (94%) but often went undiagnosed and untreated. When it is untreated, it can cause osteoporosis, already a danger for people with PWS. An expert panel developed treatment recommendations for women with PWS.

Parents of children with PWS should begin asking doctors about hypogonadism around the normal time of puberty.

All children with PWS should be monitored to determine if they might have hypogonadism. This is typically done by a pediatric endocrinologist, because most children with PWS are already being monitored by an endocrinologist for growth hormone therapy.

How do you know when a person is reaching puberty? In girls, the beginning of puberty is usually marked by breast development. In boys, the size of the testes increases. The typical age for the start of breast development in girls is around 10 years of age. For boys, the start of testicular enlargement is around 12 years of age.

The development of body hair and body odor are not signs of puberty.

The term used in endocrinology for the development of body hair and body odor in children is “pubarche,” which usually represents activity of the adrenal glands, called “adrenarche.” Both boys and girls typically begin to develop androgen hormones (from the adrenal glands) typically between the ages of 6 and 8, which result in the development of body hair and body odor.

The medical literature indicates that premature pubarche occurs in about 30% of girls and 16% of boys with PWS, although a more recent unpublished study estimates the incidence could be up to 60% in girls. Premature pubarche can occur as early as 5 years of age, but it should be considered premature if it occurs before 7 years of age.

Parents and caregivers can work with primary care providers and endocrinologists to identify signs of puberty, or lack of signs of puberty, at around 10 years of age for girls and 12 years for boys.

Doctors will do a physical examination to determine growth patterns and compare them to prior evaluations. If the person’s growth rate is slowing despite growth hormone therapy or the puberty seems to be stalled, this could indicate the need for further testing.

Doctors who are concerned about hypogonadism may order a blood test that measures levels of sex hormones like luteinizing hormone (LH) or follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH). Blood tests like these are usually done in the morning because that’s when hormone levels are at their highest. These tests aren’t always the easiest to interpret, but they are helpful in determining whether hypogonadism is occurring.

Monitoring for menstrual irregularities in girls can be a good way to determine the need for testing. In boys, it can be more difficult to determine testosterone levels without laboratory testing, but signs of decreased testosterone levels may include a decrease in muscle mass or a decrease in exercise tolerance.

There are also MRI or CT scan tests that can determine other reasons for hypogonadism, such as tumors or ovarian cysts.

Hypogonadism causes a number of issues because a person’s body does not undergo the usual hormonal changes around puberty. If untreated, the condition can cause:

That’s why it’s so important to stay in touch with doctors and other health care professionals to seek appropriate treatment.

The most common treatment for children diagnosed with hypogonadism is sex steroid therapy (SST). Some people refer to it as sex hormone therapy or hormone replacement therapy.

No matter which term is used, the goal of treatment for hypogonadism is to provide the hormones that the body is not producing.

For girls, that means treating them with estrogen. And for boys, testosterone.

Sex hormones are important hormones for developing children and adults.

In PWS, sex steroids are important for:

For girls, the most common treatment for hypogonadism is estrogen, which can be delivered either with estrogen patches or pills.

In early puberty, doctors tend to prescribe estrogen patches (transdermal estrogen). The patient can start with lower doses, and the amount of the hormone can be increased gradually. Transdermal estrogen and oral estrogen are processed differently by the body.

Eventually, girls will need both estrogen and progesterone (also normally made by the body) for overall health.

In boys, being treated for hypogonadism means replacing the testosterone that they are not making. This can also be done in a variety of ways.

Sex steroids are a safe and effective treatment for the hormone deficiency that causes hypogonadism. Despite success in treating hypogonadism with sex steroid therapy, hesitancy about hormonal therapy has been a significant issue in the PWS community.

It is important to remember that the therapy is replacing hormones that would normally be made by the body, rather than adding something new.

This appears to be the result of concerns about behavioral changes that might occur for boys or management of menstruation (periods) for girls.

It’s common for parents of boys to worry about behavioral changes with the start of sex steroids, particularly testosterone. However, when treatment begins with a low dose and works up to an adult dose, behavioral changes are not common side effects.

For girls with PWS, parents often express concern about having periods and how to manage them. By discussing this concern with physicians, it is possible to work together to provide appropriate estrogen replacement.

Dr. Stafford’s experience shows that a careful, slow approach to sex steroid therapy in boys results in few issues with behavioral change. And while estrogen therapy often leads to menstruation for girls, doctors can manage the frequency and timing of periods in ways that make this much easier for girls and their families.

Untreated hypogonadism can be detrimental to the health of people with PWS.

Sex hormones in typically developed individuals are naturally made by the body and provide important benefits to the individual. When people with hypogonadism are not given the hormones that they are deficient in, their bodies will develop differently. They may experience a decrease in bone density, which leads to osteoporosis. They may not experience the growth spurts that are typical, and they may have a decreased ability to build muscles. As a result, they will have less tolerance and ability to exercise.

They also may experience psychosocial effects because they lack the development of secondary sex characteristics: breasts and wider hips in girls, facial hair and Adam’s apples on males, and pubic hair on both.

Hypogonadism is a life-long diagnosis, and it is likely that persons with PWS who need sex steroids at any point in their development/adulthood will need to continue to take them for the rest of their lives.

Of course sex steroid therapy can be stopped at any time, but the important benefits it provides will stop as well.

Two recent studies from an international group of PWS expert physicians indicate that untreated or undertreatment of hypogonadism is a problem in both males and females.

The first study of Dutch males found that “untreated male hypogonadism can aggravate PWS-related health issues including muscle weakness, obesity, osteoporosis, and fatigue.”

Similarly, a study of Dutch women with PWS showed that hypogonadism often goes untreated and causes an increased risk of osteoporosis, decreased muscle strength, and decreased quality of life.

The physicians issued a set of recommendations to treat hypogonadism in men and women with PWS that are freely available to share. The treatment recommendations include testosterone replacement for males and hormone replacement therapy (estrogen + progesterone) for women.

When doctors, caregivers, parents, and adult patients all work together to monitor and address hormonal levels in people with PWS, the serious issue of hypogonadism can be controlled and treated successfully.

With careful monitoring and gradual application, sex steroid therapy treatments can help people with PWS to grow up to lead healthy, happy lives.

The Foundation for Prader-Willi Research (federal tax id 31-1763110) is a nonprofit corporation with federal tax exempt status as a public charity under section 501(c)(3).

The mission of FPWR is to eliminate the challenges of Prader-Willi syndrome through the advancement of research and therapeutic development.

Copyright © 2020. All Rights Reserved. Terms of Use. Privacy Policy. Copyright Infringement Policy. Disclosure Statement.